“…the Red Star, obeying natural forces, began to spin closer to Pern, winking with a baleful red eye on its ancient victim” -Anne McCaffrey, Prologue to The White Dragon, 1978

In this season of beginnings and endings, it seems appropriate to discuss cyclical time around the new years. As discussed in part one of this series, superficially cyclical time appears to lack the possibility of apocalyptic scenarios more commonly envisioned in linear time. Notions about “the end” require a fixed point in time to which everything leads up and after which history is irrevocably altered. Linear time possesses these qualities but cyclical time does not, or so it is thought. Nietzsche’s understanding of eternal recurrence embraces just this worldview in which nothing has, can, or will change, but this does not mean that eternal recurrence should be seen as a labor or a horror.. Everything that happens within the cycle, even the painful, should be looked upon as good, as a way to strengthen oneself. It should be loved for its own sake, come what may: amor fati, the love of fate. For Buddha, however, though time is cyclical, the circle of death and rebirth can still be transcended and escaped. In this way, a moral if not a physical apocalypse can occur; the enlightened one saves his soul as the world and all that it in it (people, things, desires, passions, sufferings) vanish, replaced by a new, incomprehensible existence. In this way, an apocalypse in cyclical time is indeed possible.

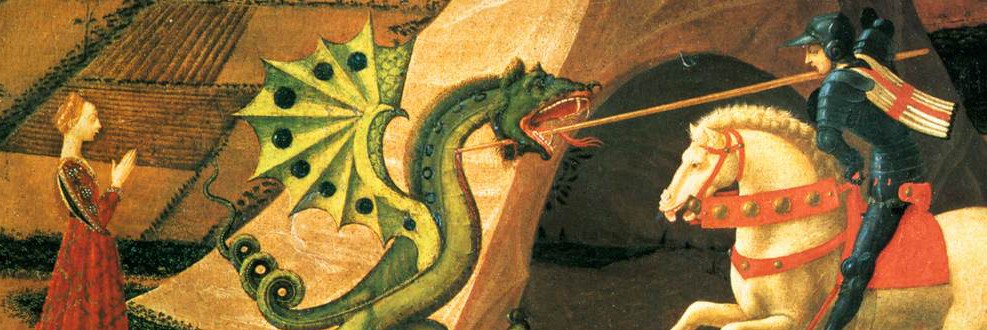

Yet perhaps these philosophical ideas are too abstract to clearly demonstrate how cyclical time and apocalyptic scenarios might work together. For this reason I have chosen to examine (very briefly) three different serial works of sci-fi/fantasy storytelling in three different media in order to show how these ideas have been and continue to be incorporated in popular entertainment. These works are Anne MacCaffrey’s Pern novels, the Wachowski siblings’ Matrix movie trilogy, and Square Enix’s Final Fantasy video game series. Each is very different from the others and are present in their own unique medium, yet cyclical time and the theme of an apocalypse runs through and unites them. Let us examine each in turn.

First, McCaffrey’s imaginative world of Pern is based upon a recurrent global crisis known as Thread, a thin, silvery, highly destructive organism that rains down from the sky for a period of 50 years every 250 years. When Thread contacts any organic material, it immediately beings to consume it, causing the organism to expand rapidly. To be sure, not all life dies out from Thread; the planet of Pern is resilient and can recover. The human populations who began to colonize Pern, however, could not survive without some defense against Thread. The danger may not utterly destroy the planet, but the cataclysmic danger Thread poses to humanity is indisputably absolute. “Thread”: it is a fitting name, not just because of the organism’s spindly appearance but also because it is simply one letter away from the word “threat.” To cope with this global horror, the colonists, before they had to abandon their advanced technology, used sci-fi genetics to adapt indigenous flying lizards into a force of fire-breathing dragons capable of destroying Thread before it made landfall. Because of the importance of these defenders, society on Pern evolved to ensure the dragons would be available whenever Thread returned. There would be 200 years of peace and safety (called an Interval) followed by 50 years of near-continuous Thread-fall (known as a Pass). During Passes, dragons and their human riders would protect the lands below. During Intervals, they would rest while recuperating their loses. It was a system that was built upon the fact that every 250 years the world would be threatened, and all of Pern society, whether directly or indirectly, was in turn based upon supporting that system. There are a few occasions in Pernese history when Thread does not fall during its expected Pass (the result of celestial alignments blocking Pern from its recurrent foe), thus creating a “Long Interval.” Though a time of joy, these periods are not without their dangers since they can cause humans on Pern to think Thread has ceased altogether, thus leading them to neglect up-keep of their dragon population. When Thread returns after its long absence, their earlier inattention becomes a deadly problem for humanity.

Using the paradigms established in Part One of this post, Pern quite clearly represents a Nietzschean view of cyclical time. Thread represents the threat of an apocalypse, but one that is familiar and manageable. Thread simply is. Like the dawn or the seasons, there is no stopping it. Once every dozen generations, the whole of humanity will be at risk of utter annihilation, and once every dozen generations humanity must try to fight off this apocalypse using their long-time companions, the dragons. Permanent destruction of Thread is impossible. Though some books in the series play with that possibility, ultimately the history of Pern is based on this eternal cycle. Ridding themselves of Thread is as inconceivable as eliminating blizzards. The proper thing for a Pernese man or woman to think about is saving the world now, this time, just like future generations should look to saving their world in their times. When the people of Pern embraced this fate, in an example of amor fati, they prospered. When during Long Intervals they neglected the fact that Thread would always be with them and thought they would enjoy linear rather than cyclical time, they lowered their defenses and risked the calamity of complete destruction. Thread is an example of an apocalyptic threat, but one that must always be seen as cyclical. False optimism only brings the possibility of ruin. But this doom is not purely negative. Pern’s society, politics, culture, and economies are portrayed as rich and vibrant. But they are at their peak only when they practice amor fati, when they shoulder the burden of Thread and yet take pride and joy in their labor and the labor of countless generations.

Turning to the second example, the Matrix series, we find a very different take on cyclical time and apocalypses. The people of Pern might suffer horrors during every Pass, but each time they are ultimately victorious. The humans in the Matrix, however, are not so fortunate. The situation goes as follows. In the future, Artificial Intelligence has enslaved mankind and imprisoned us in a simulated world from which we cannot escape unless we first understand (at least in part) its unreality. The first movie in the trilogy establishes that the humans in the real world live in the besieged city of Zion, the last bastion of humanity free from AI control. It was founded by the One, a human the people of Zion believe to be the first human to have escaped from the Matrix. The character Neo is a kind of Second Coming of the One, someone who is prophesied to bring an end to the war between humanity and the machines. At first, this seems like a very straight-forward linear time apocalypse: even casual observers will be able to note the Judeo-Christian symbolism strewn throughout the first movie. Yet the two sequels radically alter this framework. In the second movie, it is revealed that the founder of Zion was not the first human to become free of the Matrix. The One is not a rebel to the AI but is in fact part of their system: once every hundred years or so, a One emerges and the machines are able to extract useful data from his or her mind. At the same time, whatever human settlement exists in the real world is completely eradicated. The One is then sent out to found a new Zion, tell the humans the lie that he is the first and that a savior One will return to them one day, and the cycle continues itself. In the third film, the series returns to its linear mode of having Neo being the true savior of humanity that ends the war once and for all time, but this is only accomplished because the system of the Matrix begins to break down due to forces outside his control. Thus when Neo saves the day, he does not simply save humanity; he saves the machines as well.

In contrast to McCaffrey’s novels, the Matrix series, taken as a whole, constitutes a Buddhist form of cyclical apocalypse. In the first movie, people think they can live linear lives and succeed, but they are in error, just like Buddha taught that success in this world could never bring true joy. No matter what one did in this world, one would still suffer, die, and reincarnate, doomed to change in minor details but never escaping from the horrors of this world. The second movie makes this horror felt in the revelation that the machines have destroyed Zion several times in the past and have full confidence in themselves to continue obliterating humanity and allowing them to return under a new One. The machines cannot be stopped because they are part of the cycle. It is the cycle itself, not the machines, that is the real enemy. In the end, Neo abandons hope for saving himself or even for fighting out of a desire to win. To win, to finally break the system, he accepts his fate, he becomes nothingness, he allows himself to slip into the otherwise fearful embrace of a faceless existence with calm composure. Yet it is through this self-abnegation (Neo’s enemy literally turns him into a copy of himself) that Neo wins. Like Buddha, he does not simply sacrifice himself through death but gives his Self away and transcends. The result is, like Buddha, the destruction of the whole cycle of death and rebirth, or Zion’s destruction and foundation, and of apocalypse and genesis. The Matrix returns, Zion still lives, but both are suddenly new. Not just reborn but completely altered from their former station: the Matrix will no longer be a prison and Zion will be at peace. The world has transcended itself, and Neo has achieved Nirvana.

Finally, there is the example of the video game series Final Fantasy. I do not wish to focus purely on one example from the series or discuss in detail specific apocalyptic themes contained therein, though that could be done. Instead, I’d like to consider the series as a piece of media which has these elements in it. yet to do that, first a very brief overview of these themes are necessary. There are over a dozen Final Fantasy games, with most of them existing in completely different continuities or at least so distantly related as to be irrelevant for the most part. Yet while the characters and plots might vary, the games tend to share many common elements. Typically the story revolves around a band of heroes (chosen, prophesied, or impromptu) caught up in a series of escalating adventures that ultimately lead them to confront an evil so great that it has the power and will to destroy world or even unmake reality itself. Normally the cosmic terror is only revealed late in the game, with the first half being devoted to defeating a relatively minor threat like an evil warlord, an oppressive government, and so forth. Sometimes the two (the immediate and the cosmic threat) are joined together in some way, either the corrupt political/religious leader working for this great threat, exploiting fear of it among his subjects for his own benefit, or hoping for his own personal reasons that this enemy will actually succeed in its apocalyptic goals. But beyond the the apocalyptic, the cyclical time is a recurrent theme in the series, often negatively so. Sometimes, as in Pern or the Matrix, the world of Final Fantasy is based upon a great evil that is thought to be eternally recurrent; in these case, the heroes must be the ones who put a stop to this awful cycle. In such cases, those who blindly follow a Nietzsche outlook that assumes fate must be satisfied are in the wrong. On the other hand, sometimes the ultimate foe wants to destroy the world or unmake reality because of a misguided Buddhist-like desire to end suffering. For these antagonists, life is indeed a never-ending cycle of pain and misery because of countless sins but especially war. If they can end this cycle by causing or helping another being cause the deaths of all humanity, mankind would transcend all of these evils, or at least no long suffer them. But the heroes must fight this enemy, too, and find hope in life. Thus here, it is the Buddhist outlook, the desire to break the whole cycle, which is the enemy. As can be seen, the Final Fantasy series is by no means simple in its message or story elements.

Nevertheless, though Final Fantasy games may alter how they discuss cyclical time or apocalyptic scenarios, what is clear is that the franchise is based in large part upon featuring these ideas in some form in almost all of their titles. And that is what should be noted about Final Fantasy’s approach to the subject of cyclical apocalypses: the fact that it is a franchise catering to both an established fan base while trying to be engaging as new players come of age and pick up a controller. Whatever the motivations of the villains or the nature of time in each title, in the end the events that the player experiences are definitive and ultimately linear. Though there have been over a dozen games to bear the name Final Fantasy, there is never the thought that when one game is done that the ultimate evil will return to destroy the world. The heroes of the story and the player have seen to it that there is a happy ending. Yet oddly, it is because there is a happy ending that Final Fantasy has grown far beyond a single game. With each game released, players expect there to be a world-ending threat, maybe one that (in-universe) has always existed and is believed will never end, yet their job is to make sure it does. But with this accomplished, the player then has to wait with anticipation until the next linear apocalypse. Without much exaggeration, it can be said that the player hopes for an endless cycle of linear apocalypses. The eternal recurrence he hopes to stop in a fantasy world he wishes to perpetuate in the real world. In the game, he is a Buddhist; out of the game, he is a Nietzschean. He wants to save the world, once and for all, but he wants to continue doing so for all time. And, what is most startling, he is satisfied in both of these desires.

This post, long as it is, has only scratched the surface of a variety of subjects. Each individually deserves far more time than has been given to all of them together. Perhaps in the future I will come back to Pern, the Matrix, or Final Fantasy, but for now I leave them as presented here. Cyclical time also may make a comeback in future posts. For now, however, what should be taken away from this concept is the fact that apocalypses do, in fact, easily fit into such a conception of time. These three series, each taken from a completely different artistic medium, demonstrate in quite diverse ways how recent authors, movie makers, and game developers have approached the subject, yet they are only a select few among many more artists and commentators stretching back much further than the birth of either the video game, the movie, or even the printed novel. Whether time is seen linearly or cyclically, the notion of an/the apocalypse is so large to encompass both with room to spare. Hopefully by understanding cyclical apocalypses it will be possible to better appreciate linear apocalypses and how they express in their own unique way humanity’s many possible fates.

“In two thousand years, I will remember none of this. But I will be reborn again here. So even as you die again and again, I shall return! Born again into this endless circle I have created!” -Final Fantasy, 1987