“Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.”

-Charles Dudley Warner

In the first century, Jesus’s disciples asked regarding apocalyptic events, “Tell us, when will this be, and what will be the sign of your coming and of the close of the age?” (Matt. 24:3, RSV). The answer they received, and the ones that Christians shared and promoted for most of the next thousand years, had very little to do with human beings. To be sure, humans persecuted, humans were persecuted, and humans achieved or were denied salvation. But they were not responsible for the things that happened. God alone was – or, perhaps, devils, though their actions, too, were permitted by God until their ultimate destruction. Jesus advised some people to “flee” from persecution, but where to? Individually or in groups? For how long? And what were they to do after fleeing? These questions are not answered (or even asked). John of Patmos in his vision (the book of Revelation) also provides many insights into Christian apocalypticism, but Christians are nevertheless very passive players. They are victims and martyrs, always reacting to or caught up in but never responsible for the main events. The only mortals who “do” anything in Revelation are the Two Witnesses – two unnamed prophets, usually associated with Enoch and Elijah, foreordained to return to earth near the End – or evil followers of Satan. Christians are not expected to do anything but (1) resist temptation and die, (2) avoid persecution and (maybe) live, or (3) apostatize and be damned. They are never told to physically fight, proselytize, hoard material goods, live as individuals, form small-group settlements, organize large communities, advocated for a political or national cause, support a specific political or religious leader, refuse taxation, gather weapons, or, really, anything we might do today if we believed the End were upon us. In a word, Christians are not important in John’s vision of the End. But, of course they are not. Among the many ideas (most obscure) in Revelation, an important one is that God is supreme. Angels, devils, and corrupt humans are nothing compared to God. Christians, more than anyone else, need to realize that there is nothing they can or cannot do to thwart the Divine Plan. They will have no say in if, when, or how the End happens, which is reserved for God alone. So, of course it is not important what Christians do when the End begins, so long as they remain Christians.

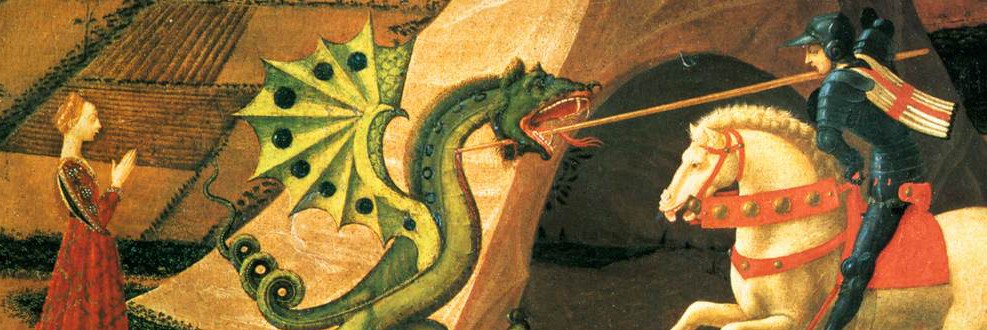

Paul in 2 Thessalonians does mention an entity known as the Katechon (τὸ κατέχον, “that which withholds”). There have been many interpretations as to what this restraining force is meant to be. Some Christians around the year 300, for example, thought it was the (at-that-time-predominantly-pagan) Roman Empire, the absence of which would trigger the End. As Roman political power began to decline, Christians redefined the Katechon when the armies of the Antichrist failed to materialized. But for the first 1,000 years of Christian history, only very rarely were Christians of any variety identified with the Katechon. In the 7th century, there was some idea that a Byzantine ruler might fit the bill, but such an argument was more interested in showing that the contemporary world’s problems couldn’t be that bad since the Katechon was still around (and would be for some time, the prophet claimed). In the 10th century, the idea was revived, and people in Latinate Europe began to wonder if the Katechon might actually be a Christian, a figure that would become known as the Last World Emperor, a person who would be the best Christian ruler ever whose abdication of his authority to Christ himself on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem would trigger the Antichrist (hitherto hidden) to make his move, thus triggering the start of the End Times. In the 11th century, more and diverse ideas of Christians having agency in if, when, and how the apocalypse would begin developed, culminating in 1099 with the military conquest of Jerusalem during the First Crusade. But the world did not end. Jesus did not return. There was no clear Last World Emperor, nor would anyone claim the title and lay down their crown in person in Jerusalem. The world continued. But so, too, did Christian speculation about what they could or should do in order to affect (and effect) the End Times.

To recount all of the things Christians have believed could trigger the start of the End Times would be endless. A short list includes:

- The formation of the Franciscan and Dominican orders in the 13th century

- Forming a military alliance with the (fabled) Christian king in the East, Prester John, to retake Jerusalem after the collapse of the Crusader States in 1291

- The forced conversion of Jews in Spain (throughout the 14th and 15th century until their expulsion en mass in 1942)

- The voyages of Christopher Columbus (who thought himself a prophet) starting in 1492, in which he was looking, in part, for the Garden of Eden, and subsequent attempts to evangelize the world expressly to trigger the apocalypse

- The Protestant Reformation (starting in 1517)

- The Puritan colonization of North America (starting in 1620)

- The English Civil War (1639/1642-1651/1653)

- The American Revolution (starting 1775)

- The foundation of the Nauvoo Temple by the Latter-Day Saints in Illinois in 1836

That is sufficient. Further examples, particularly within the 20th century, are often too depressing to speak of as things Christians have attempted in the name of enticing Jesus to return, but racism (in various forms) has often gone hand-in-hand with many of these efforts.

The point of all of this is simply to say that, since approximately the year 1000, Christians, who had previously been inclined to ask, “How will God bring about the End?” began increasingly to ask, “What should I myself do as part of the apocalyptic drama?” This question, completely divorced from the history of the early church, remains with us today. It can be seen in conspiracy theories against secret cabals, supposedly atheistic school systems, amorphous socialist plots, foreign infiltration (variously defined along racial, religious, or cultural lines), and many, many others.

The QAnon movement (some of whose members were involved in the January 6 attack on the Capitol in Washington, D.C.) is a great example of this idea. At heart, QAnon believes in a world of moral absolutism, divided very clearly between the Ultra Good and the Pure Evil (heaven and hell, in essence). There is One mortal political savior, One nation of any real value, and One providence guiding both toward higher greatness (or dismal ruin if they are not adequately supported). Here we see belief in an American Katechon – an individual whose presence preserves all goodness but whose absence unleashes all the world’s evils. This, from a secular perspective, is nonsense. From a historical Christian perspective, such ideas have existed for a long time but have very little to do with first-century Christianity aside from the façade many adherents inject into it to give it respectability among American Evangelicals. Nevertheless, there is nothing in the New Testament or the writings of the early Christians that supports the messianic ideas QAnon and related conspiracies have formed within the past few years (and especially the last few months) around the recent American election.

As has been argued by others (see, for example, Norman Cohn’s Cosmos, Chaos, and the World to Come), the idea of an “apocalypse” – of a point in time in which the good-who-suffer and the evil-who-prosper receive what they truly deserve – appeals to a human desire for a world that is sensible and just. Most want such a world to exist now while also admitting such is not the case. “Apocalypse” reassures believes that such a time will come, but they must be patient. But John of Patmos knew that waiting is excruciating. “When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne; they cried out with a loud voice, ‘O Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before thou wilt judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell upon the earth?'” (Rev. 6:9-10, RSV). People want meaning, often in the form of a just world. And it is good to strive for a more just world. But when conspiracies of satanic cabals lead people to ignore science and facts, to reject reasoned expertise, to fear the Other, to shun nuance and debate for moral absolutism, to avoid national self-critique, to embrace heroic myths rather than historic reality, to promote an individual’s cult of personality above democratic processes, to demonize opponents, to ascribe nothing but political motivations to conclusions that do not support one’s own world view, and to believe one’s own actions are of apocalyptic significance in the Ultimate Battle Between Good and Evil – when that happens, participants are not promoting a more just world. They are inflicting injustice upon others. In attempting to fulfill the apocalypse and to bring about a utopian world, or to protect someone or something they believe to be a Katechon keeping back all the hordes of hell, that is, to not just talk about the weather but to do something about it, they are, in fact, rejecting an older Christian apocalyptic tradition in favor of a newer (and arguably more destructive) one.

“If the clouds are full of rain, they empty themselves on the earth; and if a tree falls to the south or to the north, in the place where the tree falls, there it will lie. He who observes the wind will not sow; and he who regards the clouds will not reap. As you do not know how the spirit comes to the bones in the womb of a woman with child, so you do not know the work of God who makes everything. In the morning sow your seed, and at evening withhold not your hand; for you do not know which will prosper, this or that, or whether both alike will be good.”

-Ecclesiastes 11:2-6 (RSV)