Death: When next we meet, the hour will strike for you and your friends.

Block: And you will reveal your secrets?

Death: I have no secrets.

Block: So you know nothing?

Death: I am unknowing.—The Seventh Seal, 1957, dir. Ingmar Bergman

Last October, I gave a lecture to a medieval history class about apocalyptic beliefs. I opened the class the same way I have similar ones. I asked, “What does ‘apocalypse’ mean?” (My advisor starts his apocalypse course in a similar way, and I have adapted his approach.) The answer, even from some of the non-traditional adult students, was typical. They defined it as a disaster, the end of all things, human extinction, the end of the world, and so forth. I think the vast majority of people would give the same answers. They are all right in terms of popular culture, but quite wrong when discussing the apocalypse until relatively recently.

“Apocalypse,” derived from Greek, means “to unveil” or “to reveal.” That is why the last book of the New Testament is called variously The Apocalypse or The Revelation of St. John of Patmos—it is the vision “revealed” to him of future events. There is a long series of changes in the history of the word, but it isn’t too hard to understand that, over the course of 2,000 years, the word for the knowledge John received became a shorthand for the book he wrote, which in turn came to denote its frightening contents. While “apocalypse” will almost universally be used today to mean something horrible of global significance, it is important to not forget its use and meaning in days long past.

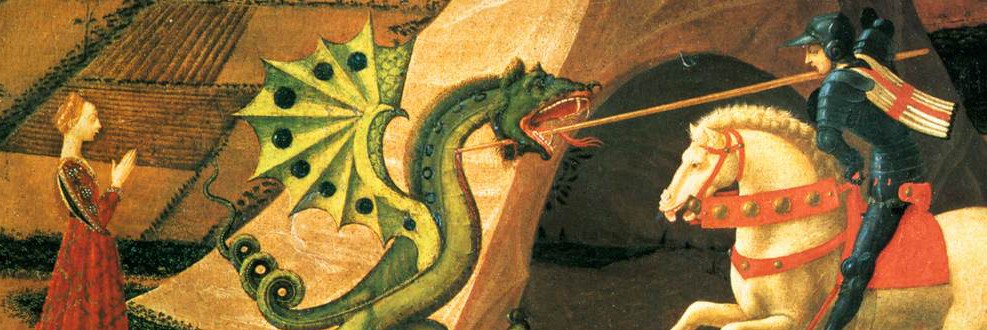

As scholars have discussed (but especially Norman Cohn in his book, Cosmos, Chaos, and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith), the concept of linear cosmic time is relatively knew and was an innovation from cyclical cosmic time. In other words, long before the Abrahamic faiths, people in the Near East tended to believe in gods of order that were part of an endless struggle with the forces of chaos. Victory was always temporary, and renewal was a typical motif for these ancient religions. When monotheism began to develop with the Hebrews and Zoroastrians roughly 3000 years ago (though the timing is quite debatable), the traditional view of the cosmos began to change. These people believed in one God who was not only all powerful, the maker of heaven and earth (which might also be subject to ultimate destruction), but was also a moral judge, a being who cared not just for maintaining a static cosmic order by any means necessary but one who wanted things done according to a code of right behavior. These two ideas came together in trying to solve the problem of evil: why do bad things happen to good people and not only to bad people? The answer for previous peoples had been: if you suffer evil, you must have deserved it somehow. The new answer, however, was tied closely to a monotheistic god’s absolute power, his role as moral judge, and the belief in a finite amount of time to human history (that is, linear time leading to a conclusion rather than cyclical time continuing forever). This new answer was: if bad things happen to a good person now, in the world to come after this life, God will provide the perfect judgment for eternity that is lacking in this present life, even if we don’t know or can’t understand it yet. In other words, the mystery of why good people suffer will remain hidden until a later day when God will reveal the truth, and we will understand his ultimate purposes. Since that answer was formulated many centuries ago, there have been people who have claimed to have received special revelations about what is hidden behind the veil that separates human knowledge from divine knowledge. John of Patmos, the author of the last book in the New Testament, is one such person, though there are many others. Because “apocalyptic” knowledge of the future was closely tied in with awaiting the just reward for good people who had suffered and the righteous punishment of the wicked who had prospered, many apocalypses tended to speak of violence before humanity would received complete divine understanding, but apocalypses certainly did not require such horrors. Nevertheless, it is John’s vision of dragons, beasts, the four horsemen, two-faced leaders, plagues, global disasters, and wars on earth and in heaven that most people in the United States think of when they consider “apocalypse” in a religious sense. Modern secular apocalypses owe much to John as well, even when spiritual matters are the least of their concerns.

The shift in meaning for “apocalypse” carrying the sense of an “unveiling” to one of death and destruction, as I said, is a long one. I think, however, that world events in the first half of the 20th century greatly helped to encourage the more recent definition. Art also played a large part. The 1957 Ingmar Bergman classic, The Seventh Seal, is a prime example, coming at about the time when the old definition of “apocalypse” ceased to have much meaning for the general public. The story of The Seventh Seal follows a knight named Bloch, his cynical squire, and companions they meet along the way. The story takes place during the Black Death, a time in the 14th century when 1/3 of people in Europe (not to mention huge numbers in Asia and North Africa) died of the bubonic plague. Bloch, returning home after many years away, sees the widespread death around him. He does not fear death as such (he even plays a friendly game of chess with a personified Death in order to buy himself time to get home). No, what troubles Bloch is not death but the silence of God. It was Hamlet’s “undiscovered country, from whose bourn no travel returns,” that gave him pause. Block refused to believe like his squire that nothing but oblivion awaited us after death, but he lacked any evidence to refute him. At one point, Bloch speaks to a young woman (condemned to be burned as a witch) to see if he could have a word with Satan. Surely he must know something about God! But the devil does not come. Even Bloch’s banter with Death over chess gives witness to the knight’s hope that he will be able to peak behind the veil and gain some assurance that there is a divine plan and what it might be. When Death says he cannot answer Bloch’s questions, he explains that it is not because he as Death has secrets to keep or because he knows nothing. Rather, he says, death is the antithesis of knowledge. “I am unknowing.”

The story of The Seventh Seal highlights (though I will not say “caused”) the change in modern culture when “apocalypse” lost its old meaning of “to reveal” and took on the now ubiquitous sense of death and mass destruction. The Seventh Seal is certainly an apocalyptic movie. Indeed, the title is a reference to a art in John’s book. But it is apocalyptic in both senses of the world. It is a story about a man wanting to received a revelation, but one that he is never given in life. It is also the story of the Black Death, when millions were dying and one might have thought the Last Days were at hand. I think most people, if they saw The Seventh Seal and then were asked to explain if, how, and why it was “apocalyptic,” would answer, “Because of all the death from the plague. But it wasn’t really an apocalypse, I guess, because the world didn’t end.” But I think someone with an understanding of the older meaning of the word would see the movie as apocalyptic because of Bloch’s agonizing search for meaning. I have not studied this aspect of the film’s production, but I strongly suspect that is the sense Bergman would have favored.

Over the last half century or so, as society has moved away from believing wholeheartedly in divinely ordained universal truths—thus reducing the drive for revelation in most people’s lives—while becoming ever more aware of potential world-ending events, it makes sense that “apocalypse” has transformed its meaning. Death is easier to imagine than the unimaginable knowledge of God. We—even those among us of faith—have largely consigned ourselves to the belief that there will be no new revelation in this life. Like our ancestors thousands of years ago, puzzling over the problem of evil, we can only say that Heaven remains silent, at least for now.

“And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour.”

—Revelation 8:1, KJV